Creative industries still locked behind a class divide, warns the Sutton Trust

New research reveals the extent to which the creative industries remain elite professions. According to the Sutton Trust’s new report, there are stark overrepresentations for those from the most affluent backgrounds (defined in the research as those from ‘upper-middle-class’ backgrounds). And those who were privately educated also disproportionally occupy top roles in this sector.

The report reveals that among those aged 35 and under, there are around four times as many individuals from middle class backgrounds as working-class backgrounds in creative occupations. Yet while just 20 per cent of the UK’s working-class individuals in employment have a degree, three times as many working-class people in creative jobs have one. The Sutton Trust said this underscores the importance of equal access to higher education for all young people.

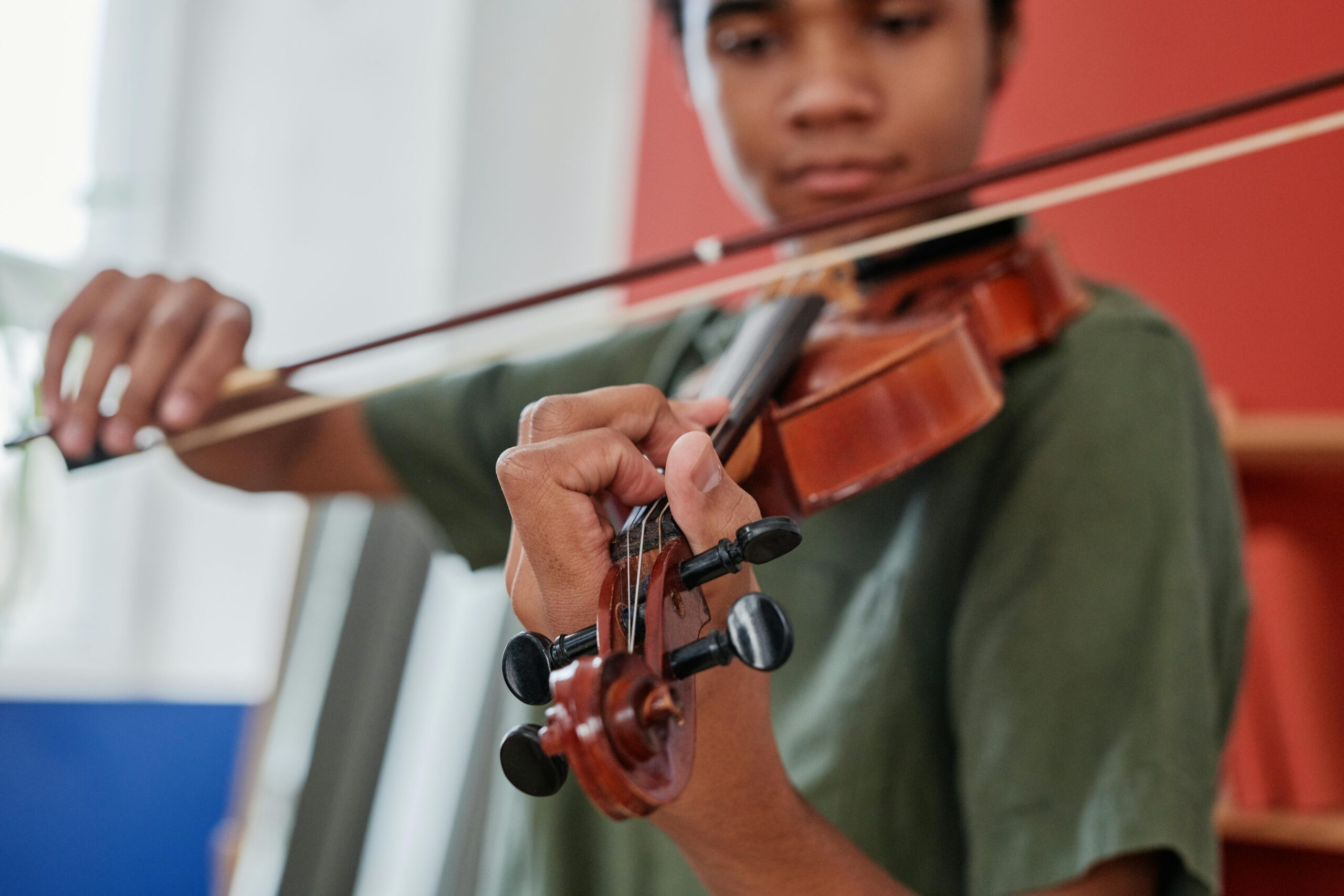

Education and class background have a huge impact on people’s ability to reach the top of their creative profession, according to the report. Across television, film and music, high-profile figures in the creative industries are much more likely to have attended private school than the UK population. BAFTA-nominated actors are five times more likely to have attended a private school, at 35 per cent compared to the national average of just seven per cent.

Classical music is a particularly elitist profession. 43 per cent of top classical musicians have attended an independent school (over six times higher than average). Additionally, 58 per cent of classical musicians have attended an arts specialist university or conservatoire, and one in four attended the Royal Academy of Music for undergraduate study. These institutions are dominated by students from the most affluent backgrounds. 12 per cent attended Oxbridge.

However, pop stars appear to better reflect the education backgrounds of the UK population as a whole. Only eight per cent were privately educated, and 20 per cent attended university, both close to the national averages.

64 per cent of top actors have attended university, with 29 per cent attending specialist arts institutions (including conservatoires). Nine per cent attended Oxbridge and a further six per cent attended other Russell Group institutions.

Research shows that access to creative degrees in subjects such as music and art is skewed towards those from upper-middle-class backgrounds at the most prestigious institutions. At four universities – Oxford, Cambridge, King’s College London and Bath – more than half of students on creative courses come from the most elite ‘upper-middle-class’ backgrounds.

The universities with the lowest proportions of creative students from working-class backgrounds are Cambridge and Bath (four per cent), Oxford and Bristol (five per cent), and Manchester (seven per cent). At each of these universities, the percentage of creative students from working-class backgrounds is lower than for students on all other degrees (six per cent at Oxford and Cambridge, seven per cent at Bath and Bristol, and 19 per cent at Manchester).

There is also a ‘stark class divide’, says Sutton Trust, in specialist institutions such as conservatoires and higher education institutions specialising in music and the performing arts. The Royal Academy of Music (60 per cent), Royal College of Music (56 per cent), Durham (48 per cent), Kings College London (46 per cent) and Bath (42 per cent) all have very high proportions of privately educated students studying creative subjects. All of these institutions have higher proportions of privately educated creative students than Oxbridge (32 per cent).

Over half of Oxford, Cambridge and KCL’s music students come from ‘upper-middle-class’ households, and for six Russell Group institutions this proportion is between 40 to 49 per cent.

To tackle this inequality, the Sutton Trust is calling for a range of measures to improve access to the arts, such as introducing an ‘arts premium’ so schools can pay for arts opportunities including music lessons, ensuring that conservatoires and creative arts institutions that receive state funding are banned from charging for auditions, and adding socio-economic inclusion as a condition of employers receiving arts funding.

The Sutton Trust is also developing a partnership with the British Screen Forum, which aims to address socio-economic diversity through targeted skills and career initiatives.

Nick Harrison, CEO of the Sutton Trust, said: “It’s a tragedy that young people from working class backgrounds are the least likely to study creative arts degrees, or break into the creative professions. These sectors bear the hallmarks of being elitist – those from upper-middle-class backgrounds, and the privately-educated are significantly over-represented.

“Britain’s creative sector is admired around the world, but no child should be held back from reaching their full potential, or from pursuing their interests and dream career, due to their socio-economic background.

“It’s essential that action is taken to ensure access to high quality creative education in schools, and to tackle financial barriers to accessing creative courses and workplace opportunities.”

Responding to the research, Paul Whiteman, general secretary at school leaders’ union NAHT, said: “We have lauded the new government’s calls for ensuring every child has the opportunity to develop creative skills and access creative subjects.

“These findings from the Sutton Trust are the sad legacy of the previous government which restricted and distorted that entitlement using narrow performance measures to drive curriculum and qualification choices in schools.

“That misguided approach means that students now have very limited choices over their Key Stage 4 qualifications. The rigid and prescriptive set of GCSEs which form the EBacc narrow the curriculum, and those effects can clearly be seen in students’ post-16 choices too.

“To encourage and enable all students to study a broader range of subjects, including the creative arts, the government must reduce the content of the overcrowded curriculum and make changes at Key Stage 4. These should include scrapping all performance measures based on the EBacc subjects and reviewing the Progress 8 measure of the progress pupils make between the end of primary school and the end of Year 11.”